The better your team communicates, the more time you can spend on the fun stuff -- building interesting things and solving hard problems. When you're looking for ways to improve communication, take a look at Github. They’ve rolled out two features that should be incorporated into any project: Pull Request templates and Issue templates. In this post, I’ll walk through these tools and how to leverage them on your next (or current) project.

For sample code, and a cloneable project template (hint hint), see my gh-docs-boilerplate repo. 💅🏻

Pull Request Templates

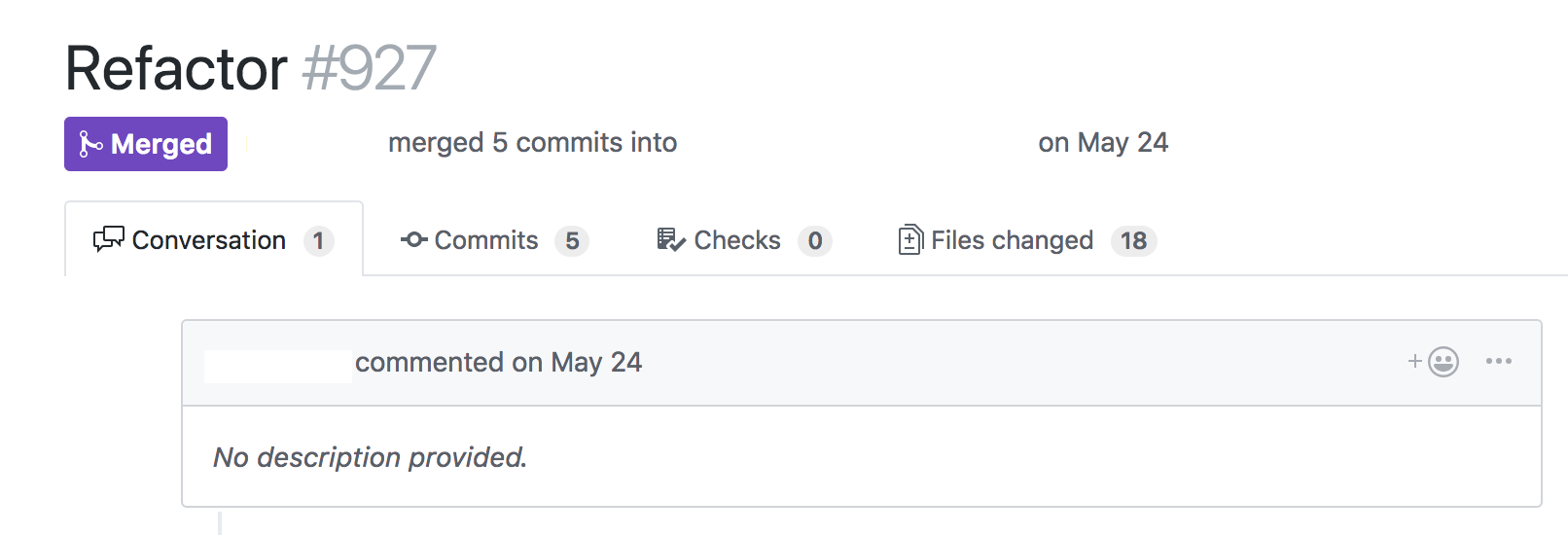

We’ve all been there: a pull request rolls in, titled “Updates”, with no description and 22 files changed.

👍🏻 LGTM

We’re not sure what it does, which tickets it closes, or how to test it. Until the person who opened the PR is given a chance to explain themself, project managers and fellow engineers can’t track on what work has been done. Over time, this lack of context and consistency slows work down and leads to misunderstandings.

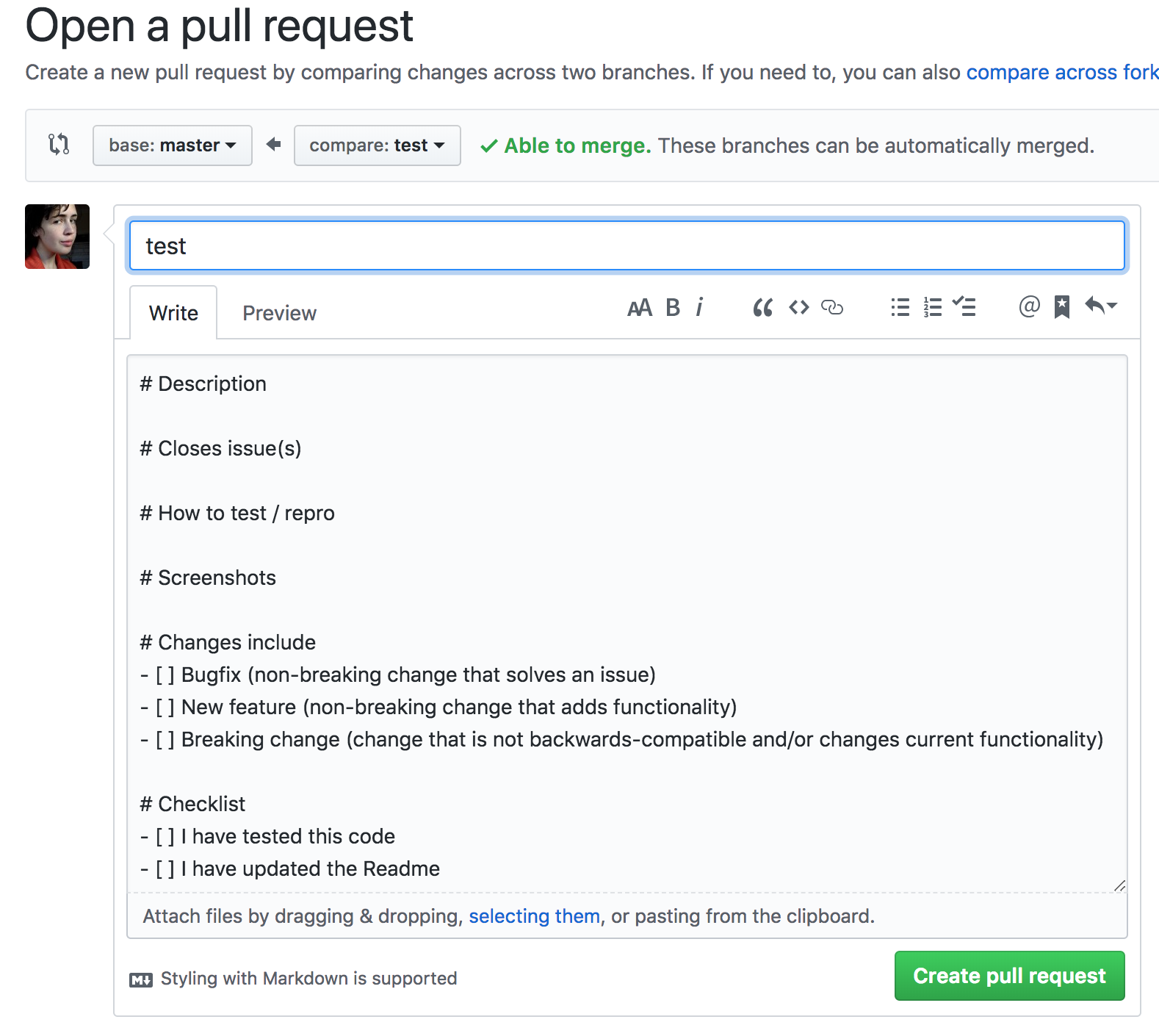

Enter Pull Request templates. These are simple Markdown files that prepopulate pull request description fields. You can put this template in your repository root, a /docs folded, or a /.github folder. Once it exists on your default branch (usually master or dev), its content will flow into all newly opened PRs.

One click and you're halfway there.

Here’s my starter template; I like to list out headings for any information I want from a contributor. You almost certainly want these questions answered:

- What changes does this branch contain?

- What issues/tickets does this branch close?

- How can I test this code?

Depending on your project and workflow, you may want to include places for contributors to upload screenshots, link to prototypes, or (my favorite) embed GIFs that reflect their feelings towards that PR.

Sample GIF included for your inspiration.

Issue Templates

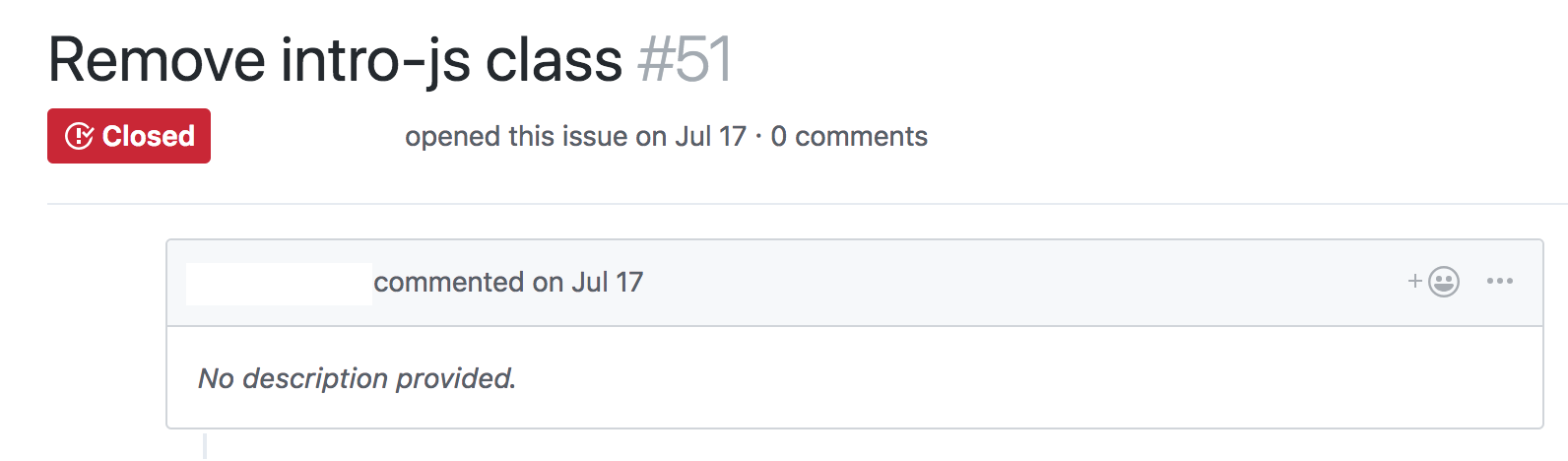

Communication and documentation can also be skimped on when opening issues. We’ve all been guilty of creating issues with vague titles and no context.

Time for some detective work!

If I didn’t personally open this ticket, I don’t know what needs to be done or what success looks like. I can’t prioritize it or estimate its complexity.

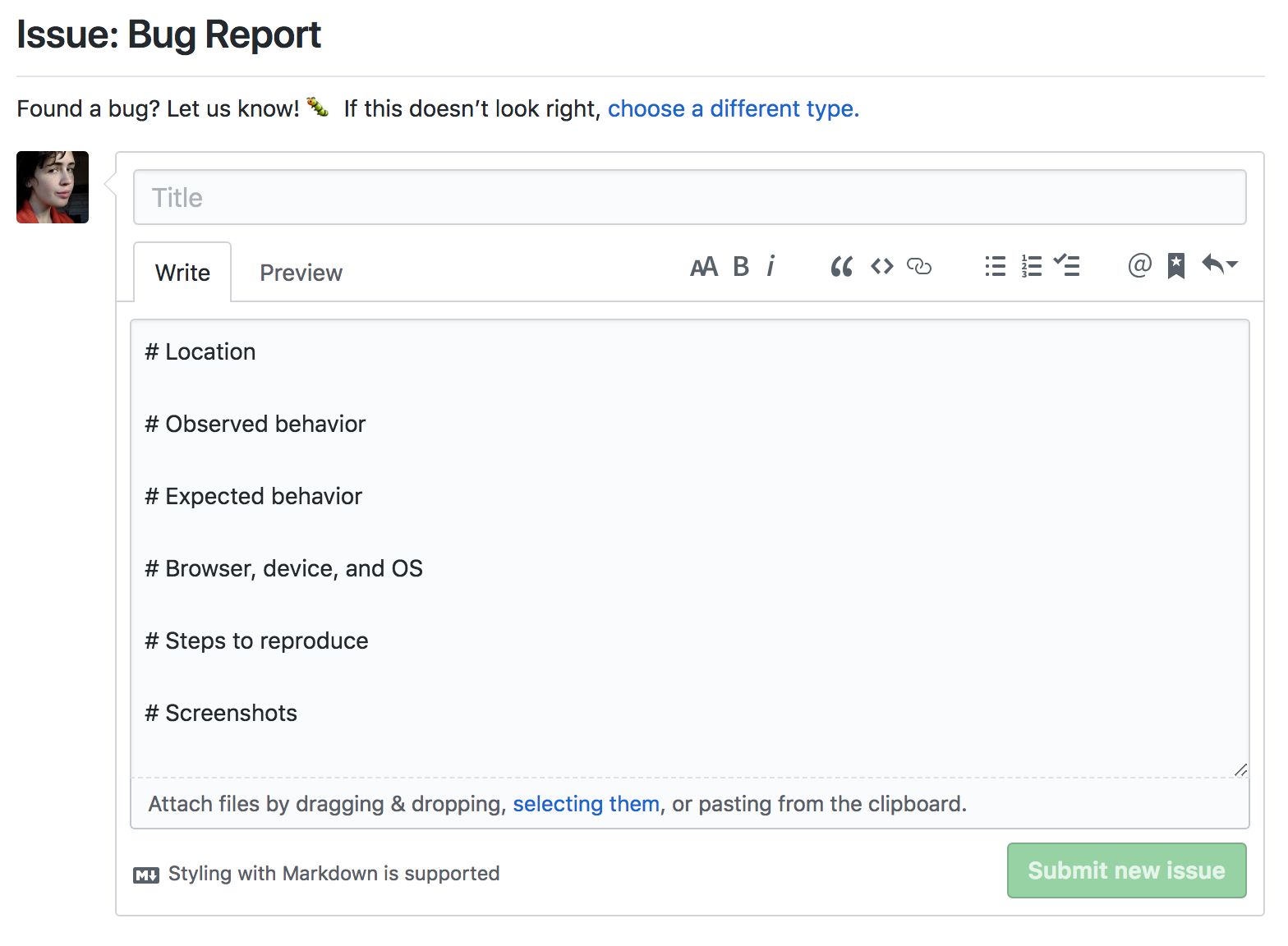

Issue templates, like PR templates, are Markdown files that provide default content for Issues opened via Github. They go in the /.github/ISSUE_TEMPLATE folder. Like PR templates, they only kick in when on your default branch.

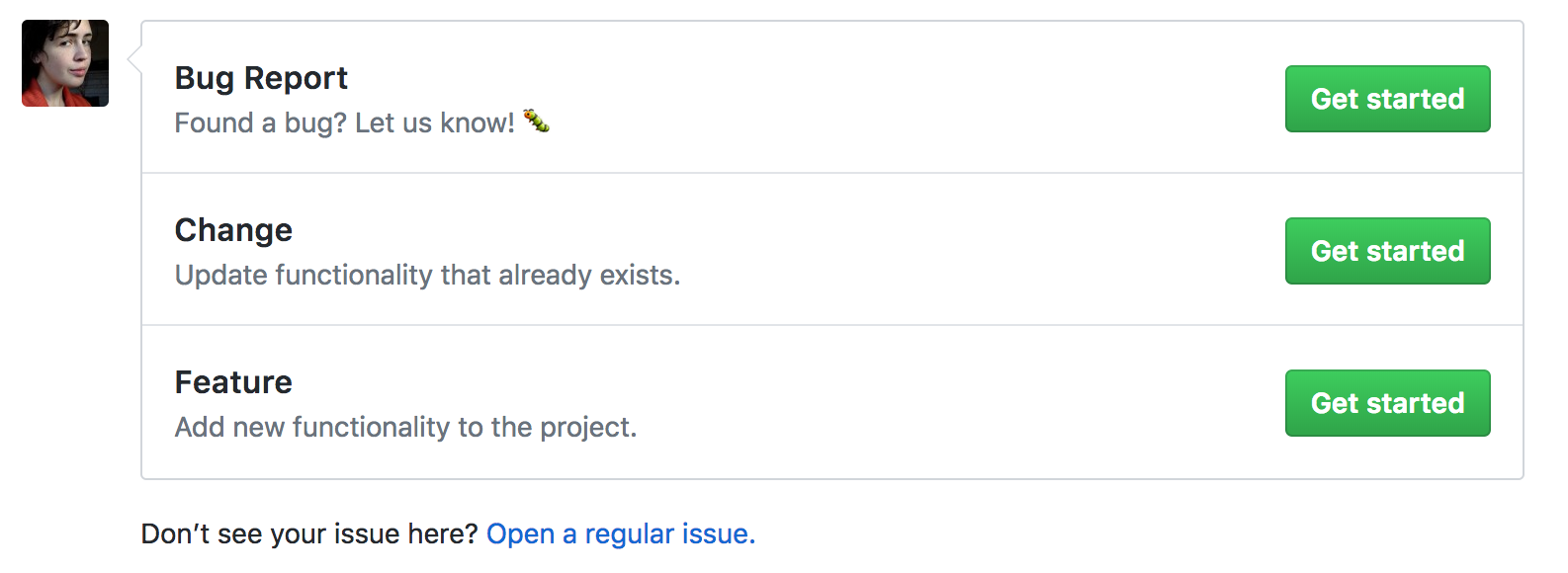

Issue templates go one step farther than PR templates by letting you create multiple issue types, which are all available in a choose-your-own-adventure issue picker.

Selecting an issue type will flow that specific template into your new issue.

You can define as many issue formats as you want and tailor them to your project. For example, a recent project of mine had five total template types. The Backend template had a prompt to list out any tests that should be written; the Frontend template asked for embedded design comps.

I recommend having at least three issue templates:

- New Feature

- Change Request

- Bug Report

These buckets encompass almost all changes made to a project. They help team members include the right information (no more bug reports without browser/OS), and they also help define the task in the first place. Knowing, and making explicit, whether something is a bugfix or an update, a change or a new feature, helps clarify its implications and priority.

I have three issue templates set up here. I recommend writing your own set of templates to reflect your ticketing flow and project needs.

In the Wild

Congrats, you added PR and Issue templates to your project! 🎉 As your project evolves, revisit them every so often to make sure they still meet your needs. It only takes a few minutes to add and remove fields, swap out or edit templates. Give any changes about a week to sink in; if they still don’t feel right, group up with your team and figure out something better. It’ll be a quick meeting, and you’ll get to learn about what each other do and need.

But Wait, There’s More!

Github offers other low-effort ways to improve communication:

The Readme

This is a low bar to clear, but I’m regularly shocked by how many projects don’t have a proper Readme. A brief write-up on what the project does and how to install it is invaluable. Even if your project is a fork or clone of another project, update your Readme — surely something about your project is different from the source material.

Code of Conduct

Adding a Code of Conduct to your project is easy, and it’s a powerful way to manage community on open-source projects. If you add one to your repo, it will be linked to in the issue creation flow.

Contribution Guidelines

Like a CoC, Contribution Guidelines clarify community standards and keep discussion productive. This will also be linked to when issues are opened. Contribution guidelines and CoCs are most applicable to open-source software, but it’s never bad to codify expectations, even within a closed team.

TL;DR

Better communication = more time building fun things. Github can help you. Use my boilerplate to make Pull Request and Issue templates, sit back, and enjoy the clarity 😎